What parents under my care think is typically different from what I think. Their concerns and fears are often removed from the reality of my thinking. That’s not a judgment, it’s a recognition of differences of how we frame and approach problems as health professionals.

I say reflux, you think cancer

One example is the conversation after a routine upper endoscopy for acid suppression resistant reflux. We look to look for chronic, erosive disease and to rule out things like eosinophilic esophagitis.

Invariably in the consult room when discussing findings I hear, (rocking, eyes closed with praying hands together held in front of the lips) “So there’s no cancer? Oh, sweet Jesus … THANK YOU.”

No matter how many times I hear this, I still find it astounding.

So while cancer may have been confidently, extensively, and unequivocally eliminated from the differential during our frank and extensive whiteboard discussion a week earlier, it remains the leading concern from some parents who’s children struggle with the most basic problems.

Fear drives so much of what we do

Sounds crazy, right? Not if you’re a parent. Fear, I’ve always suggested as a pediatrician, keeps kids alive. Fear has worked for us as a species. We’ve continue to live to see the next generation.

’There’s no cancer’ is about the disconnect. I’m there for allergic disease of the esophagus. Mom’s really there for that, for sure. secretly, however, she’s concerned about the thing that killed her cigar smoking, brandy sniffing, 87-year-old grandfather.

I think this is different from the hidden agenda. That’s where the patient or surrogate shows up with one thing in mind. It’s the one reason they’re there.

As an example, there was the school-aged child in clinic with the complaint of non-specific abdominal pain. When I casually asked about concerns and theories, she disclosed that two children in her part of town had been diagnosed with Wilm’s tumor. She concerned with this as a possibility. The pain it turns out was not that significant.

Bridging the doctor patient divide is about looking through the patient’s lens

Bridging the doctor patient divide is less about keep mama happy and more about understanding her perspective. Trying to see the world through her lens is the first step to addressing her issues and keeping her happy.

If you visit me in my office I always will ask you,

- What do you think is going on?

- What’s your biggest concern/what’s bothering you about this?

If you don’t tell me, I can’t see your frame of mind. I can’t bridge the doctor patient divide. And what I do to help you is framed only by how I see the see the signs and symptoms. I think Helicobacter pylori infection of the stomach. You think cholangiocarcinoma the liver.

And yes, there are times when a patient will not disclose their darkest concerns for a variety of complicated human issues. This presents a challenge but the patient’s frame of view typically comes into cleaner view at some point during the process. As an observant health professional you have to look for it.

You have to bridge the doctor patient divide. If you don’t, the clinical encounter can be a tough for everyone.

Bridging the divide is like managing expectations but different.

If you like this, you might like the 33 charts Doctoring 101 Archives. It’s all the stuff written here that deals with the how to of doctoring.

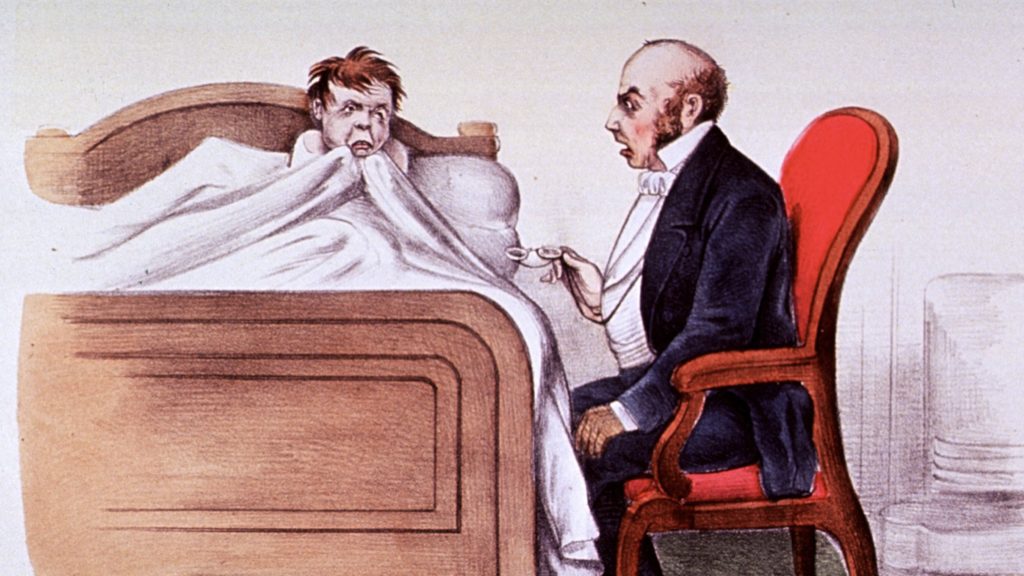

Image is via the National Library of Medicine.