Then it made sense. Because we’re in transition between siloed and networked worlds.

Our siloed world supports encounters with the health system that are isolated, episodic and dependent upon the capacity of a single provider. A networked medical world operates in real-time and is supported by decision-making intelligence that extends beyond what one person can offer.

Modern medical work is rooted in the analog. So doctors without phones, tablets or even computers do just fine. Their work requires little in the way of access. Many are modern-day empiricists doing what has been done for a few hundred years: evaluating patterns, applying intuition based on personal experience, and delivering therapies based on what’s been proven for swaths of people.

For advancing medical fields dependent upon precision diagnostics and therapeutics, a world supported by personal judgment alone won’t be sustainable. Consequently, doctors will be unable to work without access to mobile tools of information, communication, and diagnosis (connected tablets, smartphones, and glass).

While our current ability to connect the right information to our clinical encounters is primitive at best, this will evolve. And handheld or brow worn appliances will represent required elements of the physician’s expanding outboard brain.

Sure, there’s lots doctors know. But there’s more they don’t know. This is the first generation of doctors who, instead of memorizing, will access what they need to know. And as the crisis of information escalates, this access effect will become more apparent.

For now, however, some hospitals feel that doctors are better off disconnected and intuitive. And for a medical world still entrenched in the analog, this works just fine.

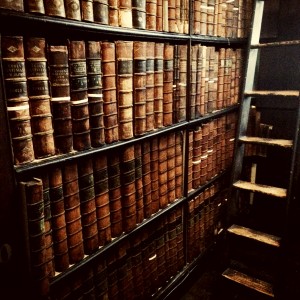

The image is one that I took in The Long Room of The Old Library at Trinity College, Dublin.